Clint Eastwood

I come from a broken home and spent my young years with my grand parents. My Nana

and Grandpa were wonderful people, but were not very firm in my upbringing. Nana

died of cancer in 1969 and I went to live with my father and step mom who already

had 2 children, I made 3. I wasn't used to living with other kids and didn't know

how to share. I was trouble for them. When I got into high school it got worse.

Then I saw a movie in school that changed my life forever.

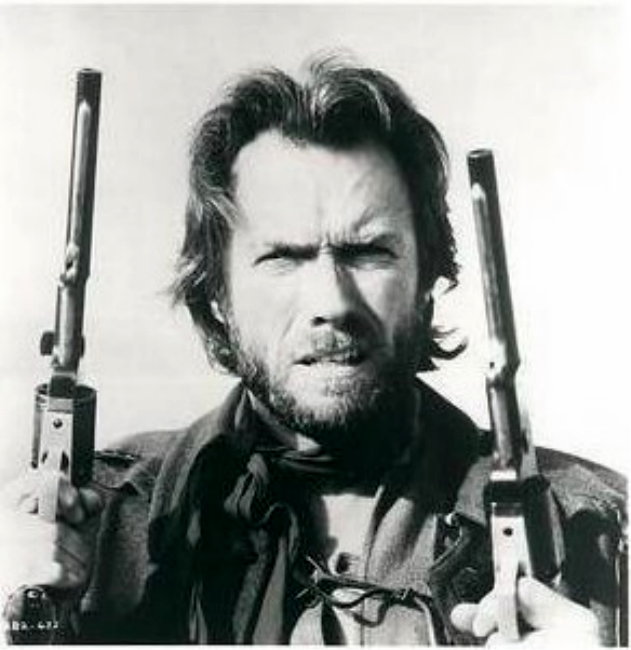

That movie was

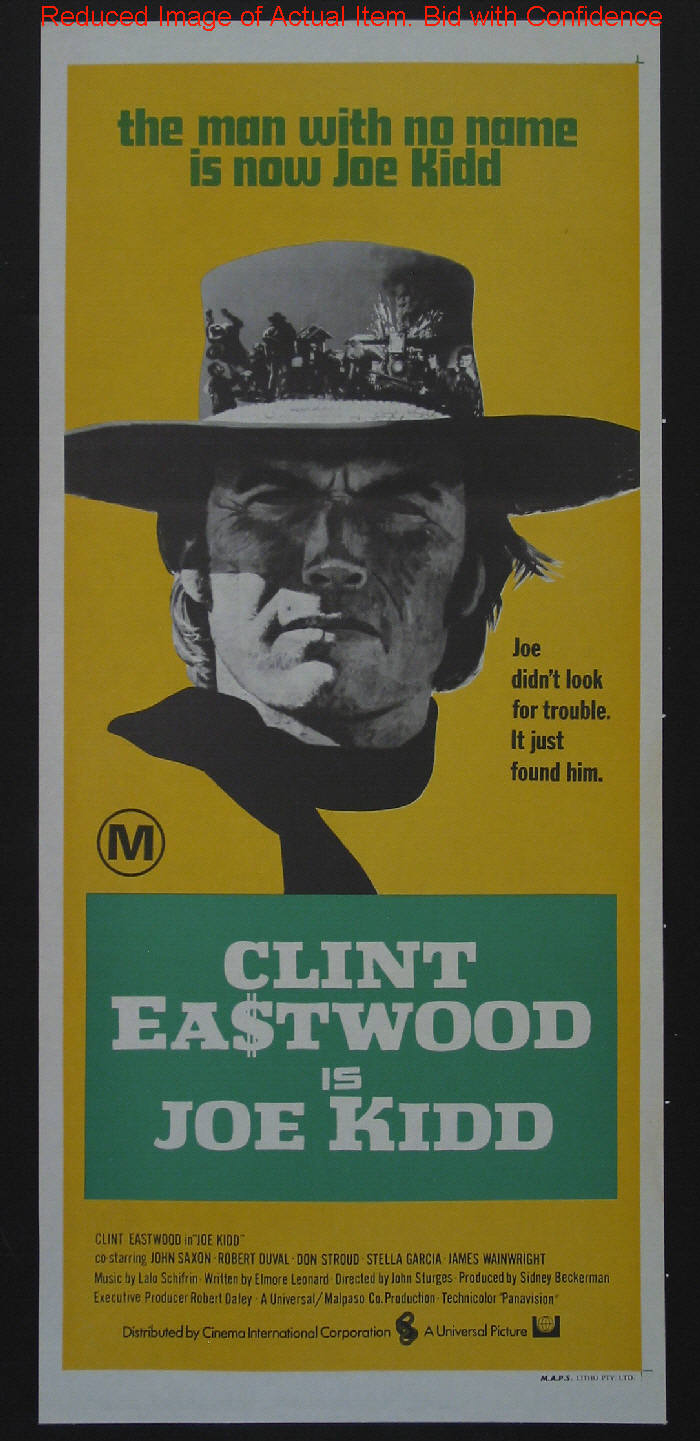

called "A Fist Full of Dollars". It stared a scruffy looking guy named

Clint Eastwood. After that Clint became my hero and roll model. My best friend

at the time was Glenn who came from a broken home too, so we could relate on several

levels, Clint became a common bond between us.

Glenn and I would search all

of Portland for theaters playing Eastwood movies. We got to know that city better

then most, and of course where all the theaters were. Glenn and I became film

experts not just for Clint flicks but Charles Bronson, Redford and Newman, Peter

Sellers, and many others. Eastwood was the alpha male, the man's man, his portrayal

of strong confident characters had a great impact on me. Because of Clint I joined

a Boy Scout explorer horse troop where I learned to ride horses and the cowboy

way.

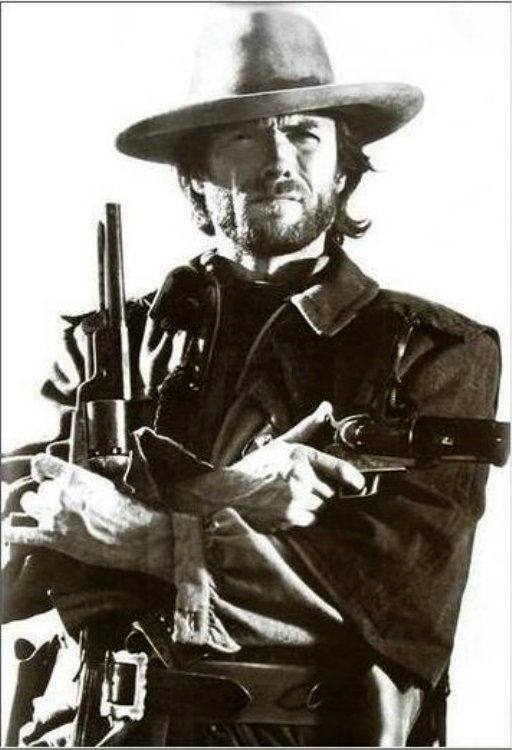

Eastwood didn't just make westerns, he was a bad ass cop in the "Dirty Harry"

Films a DJ in "Play Misty for Me, an assassin in the "Eiger Sanction",

a soldier in "Where Eagles Dare" and "Kelly's Heroes", then

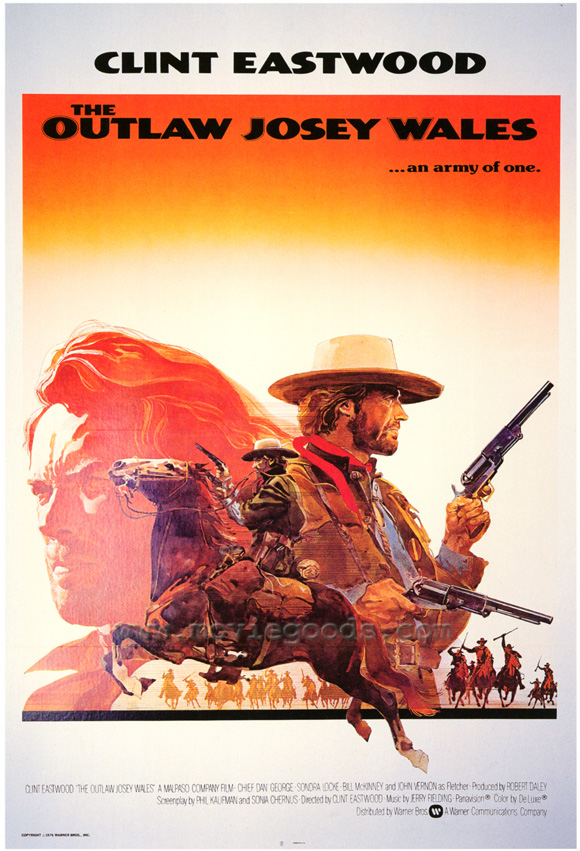

in 1976 he came back to the western with "The Outlaw Josey Wales".

My interest in movies and westerns in particular started at that time. I didn't

just want to see the films, I also wanted something from them. So I started asking

theaters for the 1 sheet posters they displayed in the windows, I would pay 1

or 2 dollars apiece for them. So started my collecting fever. It didn't stop with

posters, oh no, magazines, news paper adds or articles books, (movie tie ins and

biographies) anything I could find with his likeness or information on him.

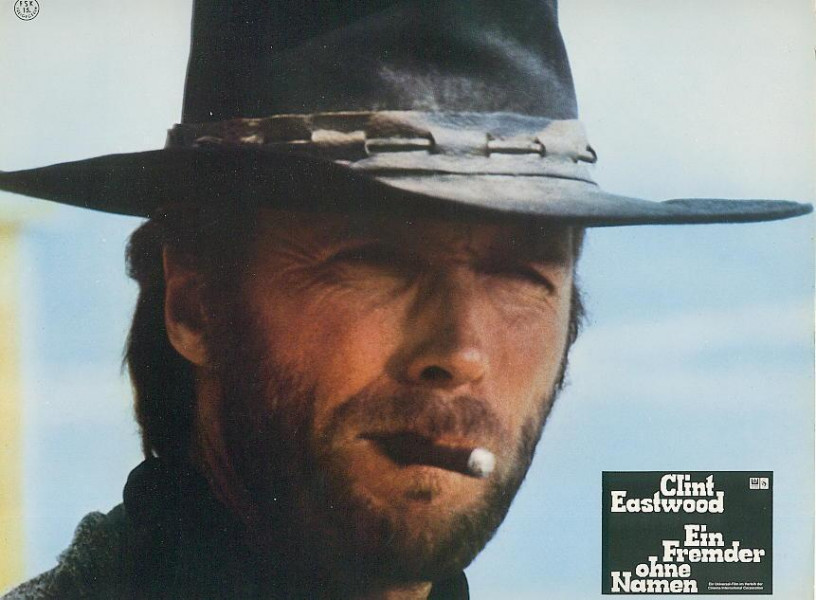

In 1977 I joined the army and was shipped off to Germany. Clint went with me.

I met my wife there and brought Clint Eastwood into her life. I found a little

theater in the town where she lived and was surprised to see the movie they were

playing was "A Fist Full of Dollars" I just had to hear Clint speak

German. His German voice was different then his own, they had a guy with a hard

deep voice do the synchronization. Afterwards I talked to the theater owner (who

spoke no English) and I not a word of German, yet I convinced him to let me have

the posters and lobby cards for the film.

Biography

The Early Years

by Richard Schickel

The first time he spoke lines to a camera, he blew them. A couple of pictures later he spoke his lines perfectly, but he was buried so deep in a dark scene that he couldn't be seen. Toward the end of his first year as an actor, he had a nice little scene with a major star on a major production, and he found a good-looking pair of glasses that he thought gave him a bit of character. But Rock Hudson thought the same thing when he saw the kid wearing them, and Clint had to surrender his specs to the leading man.

This

was Clint Eastwood's life as an eager young contract player at Universal circa

1955, and it turned out to be a short one--the studio dropped him after a year

and a half. On his own, he did what young actors do: played scenes in acting classes,

worked out at the gym, went on auditions, did odd jobs (mostly he dug swimming

pools under the hot sun of the San Fernando Valley). Every once in a while he

got an acting job--on Highway Patrol, on Death Valley Days. Once a big time show

flew him east to work on location on West Point Stories. He got to bully James

Garner on an episode of Maverick. A couple of times his heart leapt up: he got

good billing in a feature, The First Traveling Saleslady, playing opposite Carol

Channing; and he thought for awhile that he had one of the leads in another feature,

Lafayette Escadrille. But the first film was a flop, and he had to settle for

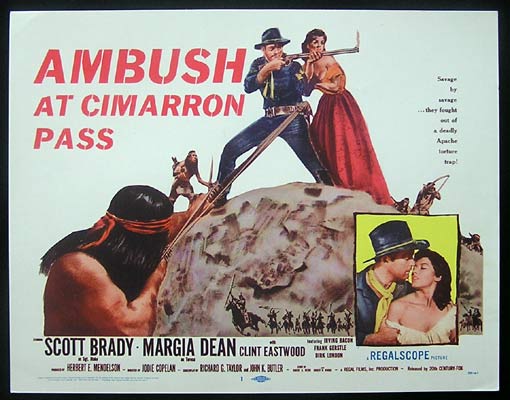

a much smaller role in the second. When he finally got a decent part in a movie,

it was in a B western so bad it almost caused him to quit the business.

In

short, his was the archetypal show-biz struggle. It ended archetypically, too.

He was visiting a friend at CBS and strolling down one of its long corridors of

power, when a man in a suit, an executive, popped out of a door, took a long look

at this nice-looking kid and asked, "Are you an actor!" Turned out he

was looking for someone to play the second lead in a western series called Rawhide

that the network was about to produce. Thus was Rowdy Yates born. Thus did Clint

Eastwood achieve his first fame and, if not fortune, then the security of a running

part in a series that lasted seven years.

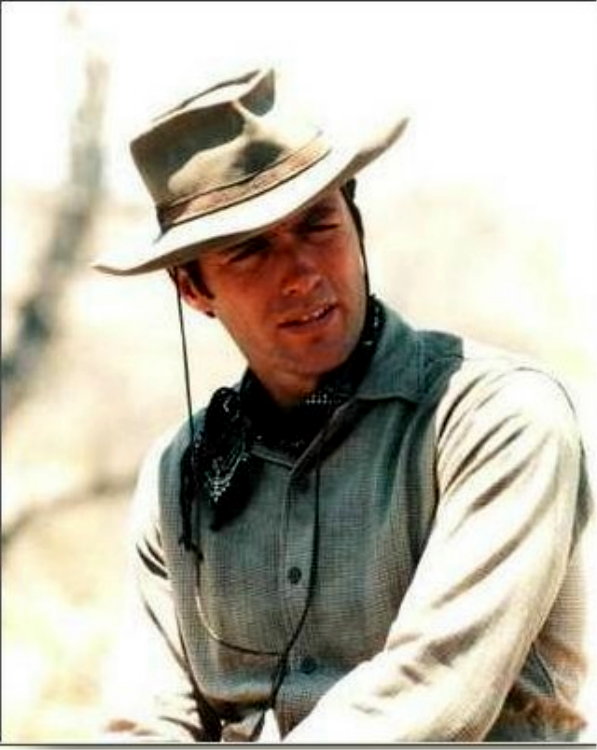

Rowdy

was like most everyone else Clint played in those years--a nice young man, politely

spoken and highly principled, but to him, not very interesting. He once told an

interviewer that he knew he "wouldn't make any impact until [his] 30s"

because in those days he still looked like he was about 18 and "had a certain

amount of living to do." Alas, he was still playing Rowdy, still in effect

a juvenile, when he reached his early 30s, which was terribly frustrating to him.

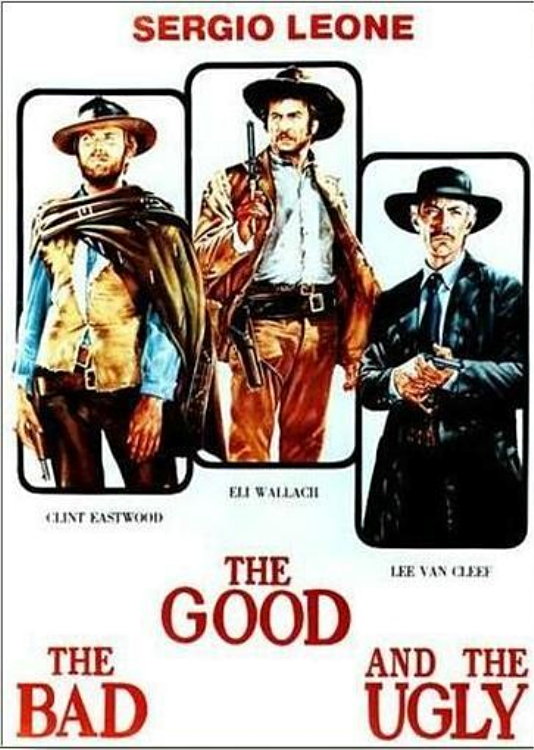

Which is why he agreed to spend the 1964 Rawhide hiatus in Spain making a western

for an unknown Italian director. The money was poor, the prestige nonexistent,

but the film that was eventually released as A Fistful of Dollars offered him

a character he had never played--a grizzled grown-up, tough and morally ambiguous.

Clint has never been given sufficient credit for the imaginative leap this

undertaking represented, for the courage it required to willfully subvert his

safe, boyish image of the time. By taking this long shot, he not only ended his

long apprenticeship, he became a true rarity--an entirely self-made star.

"I

never considered myself a cowboy, because I wasn't," Clint Eastwood once

said. "But I guess when I got into cowboy gear I looked enough like one to

convince people that I was."

To put it mildly. For actors, more than

most people, genetics is destiny. Historically, we may be sure, there were short,

chubby, talkative cowhands. Bur not in the movies, where the classic western heroes

have always been tall, thin, laconic--and flinty-eyed. Or perhaps one should say,

Clinty-eyed. Anyway, he looked the part, and he gained his first featured roles

(The First Traveling Saleslady, Ambush at Cimarron Pass), his first fame (as Rowdy

Yates in television's Rawhide, the beginnings of international stardom (in the

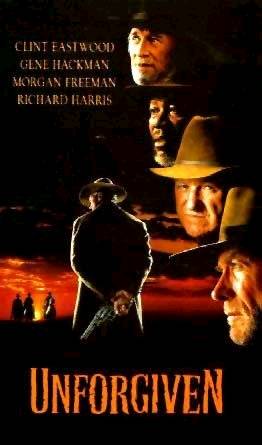

three spaghetti westerns he made with Sergio Leone) and his Academy Awards (for

Unforgiven) by acting the cowboy. When he went off to Italy to make A Fistful

of Dollars, he was thinking "the western was in a dead place, encrusted with

myth, poetry, stale pictorialism and simple moralizing." The thing that drew

him to this unlikely, low-paying project was the quality that earned it and his

other Leone films so much disapproval when they first appeared--their straightforward,

darkly comic insistence on the primitive and entirely ignoble nature of frontier

life.

Their impact on the genre was ultimately liberating--to Clint Eastwood as well as to others working in the form. In the first of the Leone films, Clint's character was styled as "a grizzled Christ figure" (to use critic Richard Corliss' phrase) who undergoes a calvary and a resurrection before bringing redemption--at the end of his gun barrel--to the hellish Mexican border town of San Miguel. In the first film Clint's Malpaso Productions produced, Hang 'Em High, his character, Jed Cooper, is hanged and left for dead in the movie's opening minutes. Rescued, he becomes a lawman who liberates an entire frontier territory from lynch law.

In High Plains Drifter, the first western Clint directed, his character quite

possibly represents a figure reincarnated to bring justice to a town every bit

as evil as San Miguel. In Pale Rider, his Preacher is unquestionably such a figure--returned

from the grave to defend the meek and the weak from their earthly tormentors.

In the two most aspiring of the films he has directed, The Outlaw Josey Wales

and Unforgiven, he plays a man broken in spirit who finds redemption through altruistic

actions reluctantly undertaken (and in the latter, more ambiguously stated).

Some

aspect of the western landscape obviously moves Clint Eastwood to thoughts of

regeneration, for it is not a subject his other films take up. Perhaps such meditations

can be traced back to his boyhood, when his parents took him to Yosemite, and

he first "looked down into that valley" and was moved to something like

a spiritual experience by the silence, the emptiness, the beauty of the place.

If ever a man were lost and needed to find himself, it is in such a place that

he might begin the search. For we find in his westerns, harsh and "realistic"

as they are in tone, that a whispered yearning for--dare one use the word--transcendence

can sometimes be heard.

Backroads & Barrooms

"Did

you once describe yourself as a bum and a drifter!" someone asked Clint Eastwood

a decade ago. "No," came the reply. "What are you, then?"

"A bum and a drifter."

Not really. Not in grown-up life, certainly.

But as a child of the Depression, he was obliged to move about constantly as his

father looked for work--most of it marginal--all over California. As a young man

trying to find himself, Clint spent a couple of years drifting around, doing hard

manual labor-lumberjacking, working in steel mills and aircraft factories. Moreover,

his lifelong passion for jazz drew him at an early age into the low dives where

the music he loved was played. All of this gave him the sympathetic sense of working-class

life, neither patronizing nor indulgent, that marks some of his best, and possibly

most enduring, work.

For most movie stars, humble beginnings are something to allude to briefly when

an interviewer is looking for a little background story. Very few of them return

to those beginnings in their work, and none have done so as consistently as Clint

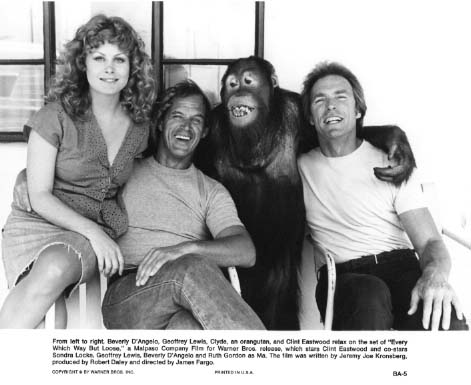

Eastwood. Just about everyone at the studio advised him not to do Every Which

Way but Loose, his lowbrow comedy about Philo Beddoe, the bare-knuckle boxer whose

best pal is Clyde, an affable orangutan. But Clint saw in the project something

of his hang-out-with-the-guys past, and audiences found in this rough, funny,

hugely profitable movie (and its sequel, Any Which Way You Can) a goofy, likable

character they could more easily take to heart than, say, his grimly taciturn

westerners or larger-than-life Dirty Harry Callahan.

Loose loosened Clint

up. It made it possible for him to relax the set of his jaw, let the ice in his

eyes melt a little, allow the droll side of his nature some play. The film helped

launch a line of work that includes two films that Clint always lists among his

own favorites: Bronco Billy, the story of an erstwhile New Jersey shoe salesman,

honchoing his rag-tag Wild West Show along the backroads to nowhere; and Honkytonk

Man, the tragi-comic saga of Red Stovall, a country singer whose largest talent

is for self-destruction. Neither ranks among his most popular films, but both

pay sweet tribute to the power of American dreaming. Both recognize, as most movies

do not, that blue-collar people can be possessed by those dreams, too.

|  |  | ||

|  | |||